Even God has a mother.

Serbian folk aphorism

When I was in kindergarten, my mom would pick me up every day after school and take me to the plaza, where I would get a bun from the grocery store. At the time it was a Dominion, which later became a Metro, then a Food Basics, and finally a Shopper’s Drug Mart. That daily bun offered a keen delight and pride I can still remember. It was an ordinary ten cent dinner roll that came loose in a plastic bin with tongs. It was oblong, crunchy outside and soft inside. Frankly, it was perfect. As we walked back to our apartment on Grenoble Drive, I would fantasize that other children were watching me enjoying the bun and burning with jealousy. I thought their jealousy arose not from the inherent value of the bun, which was ubiquitous and cheap, but from the unparalleled pleasure I took in it. How lucky I felt to have this bun every day - not only the sustenance but the ritual.

Once the grocery store changed it became difficult to find this specific, ordinary pastry. The bun became mythic, symbolic of my childhood in Flemingdon Park, which offered me fulfillment, safety, and happiness despite its shabby reality. I existed within a raft of parental love, a community of other exiled Yugoslavs who found each other in this new place, and a society of other children displaced from all kinds of global conflict and poverty, where being foreign was more normal than not.

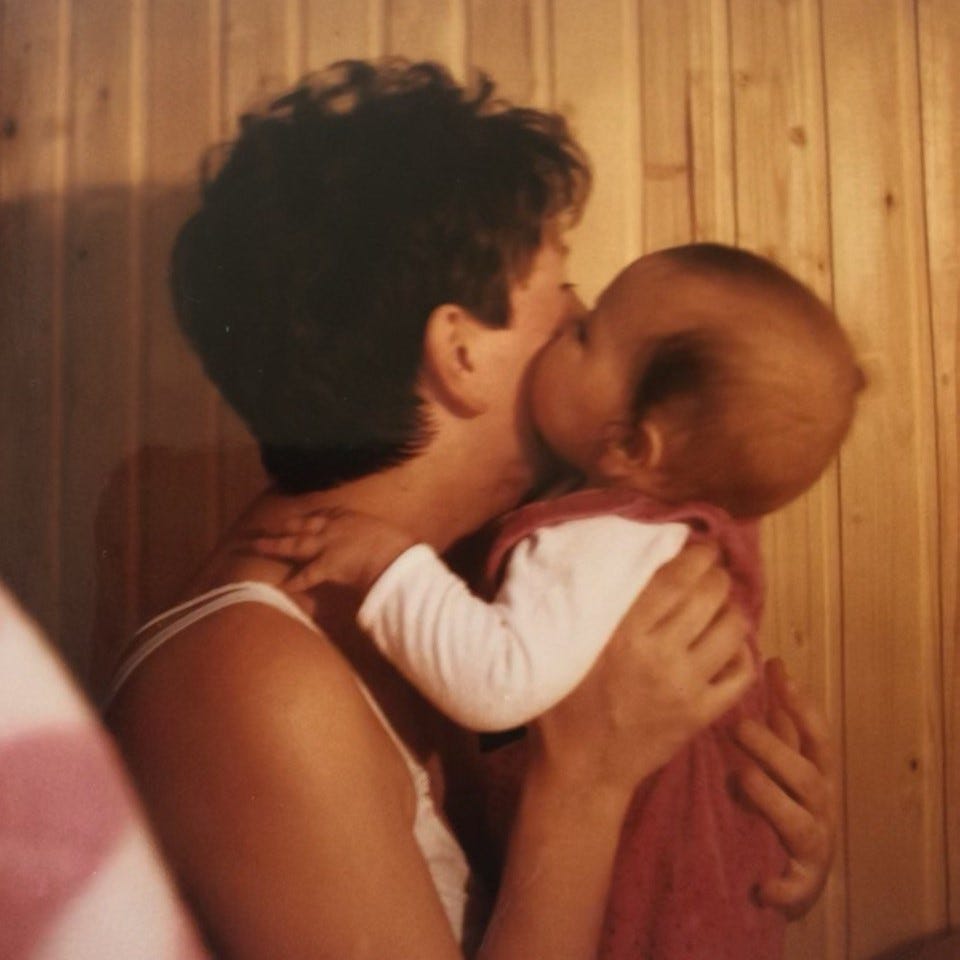

Like many childhood memories, my memory of the bun takes the presence of my mother for granted, despite the fact that the bun is really her care, her mothering. I can focus on the soft white dough inside the bun because her hand is holding mine, we are going home, and nothing bad can happen. I inhabited that maternal love so fully that it faded to the edges of my experience, providing a safe container in which I enjoyed a kind of perfect imaginary freedom. Only later did I come to know that not everyone is afforded this extraordinary privilege in childhood, either because their parents are not able to keep the external world from encroaching or because they have a different idea of parenthood altogether.

The pleasures of that time were extraordinarily simple. My dad split open watermelons on the concrete balcony. Stamps for letters home were strictly budgeted. There was contact with our besieged family members in Bosnia through the Red Cross, radio amateurs, and the Croatian church downtown. My most treasured toy was a wooden iron my dad had made for me in the Netherlands, sanded smooth.

And while I was granted this childhood, my parents dealt with having arrived in a foreign land with no possessions, taking on odd jobs as their diplomas had little meaning, ordinary poverty amid refugee resettlement allowances, illness, the pain of having family caught in the war, of having lost their homeland, their sense of belonging, their careers, their families, their house, their photographs, but escaped with their lives. I was protected from the pain of that loss even as I could not be excluded from it. They accepted the loss without bitterness; I accepted reality, and was happy.

Anthropologist Andrei Simić wrote about cryptomatriarchy in the Yugoslav family in the 1960s and 70s, describing the anti-individualistic model, where sense of family goes beyond the nuclear unit and even includes members who are dead, stretching backwards and forwards and encompassing generations with little rupture. Unlike contemporary (white) North American families, the social relationships of Yugoslav families bound “children and parents together in a system of intense emotional and substantive reciprocity” where mothers play a central role. In fact Simić locates a strong counter-current to the apparent patriarchal structure of Yugoslav society in the private realm, where women, particularly as mothers and grandmothers, gain an affective power most deeply expressed within the family. The mother gains power through her role as a mother who gives herself over to her children, who then owe her an unrepayable debt for the rest of their lives. This is not necessarily to say this is done tactically – but I do think the filial devotion is real and not unearned. It has always seemed obvious to me that Balkan women are in charge of their families, while a purported but hollow deference to masculinity is put up like a Potemkin village to appease men, who occasionally use brutal violence to reassert their unhappiness with the power of women.

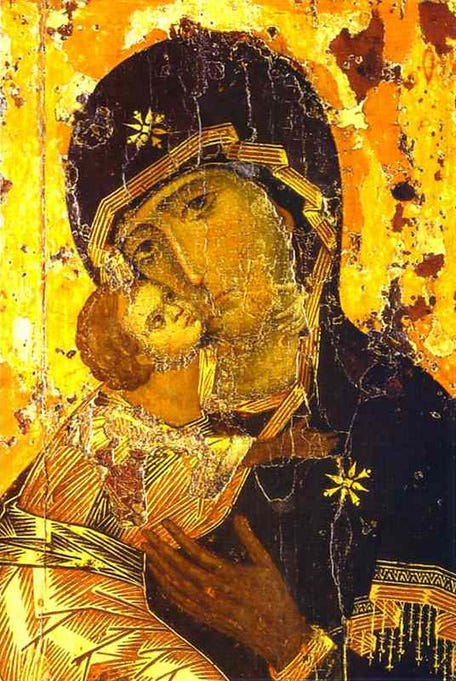

The idea of maternal sacrifice is everywhere in the Mediterranean. The mother is sacred because of her sublime altruism, the suffering she is willing to undergo for her children. Indeed until recently I confess I was unaware of the beauty of the most enduring image of Christianity: the mother and the child. Not so much a cult of the virginal mother but of perfect maternal love. In my neighbourhood, nativity scenes are beginning to be set up, while the holy land writhes in desecration and pain. Christmas, I now see, is a festival of birth, of the breast, of the ability of the mother to nourish and sustain her baby even in a barn, even as a refugee, by giving of her own body. It is about that holy devotion that is almost entirely universal. Even God has a mother - and even he can never repay her.

When I was a teenager, I visited Ephesus in Turkey with my cousins and saw the modest house in which the Mother Mary was purported to have lived out the rest of her life, after the death of her son. People prayed at the shrine as if to their own mothers. Bits of white cloth and paper were tied to a wall overfull of wishes. I now see the wooden icons of Mary and Jesus that hang in the corners of many Orthodox homes differently; as deference to the devotion of the mother, but also longing for the time when we were not completely alone, our identity and even physical sense of self enmeshed with the mother/world. Our belly buttons the very first scar of the brutal separation from perfect and sacred love.

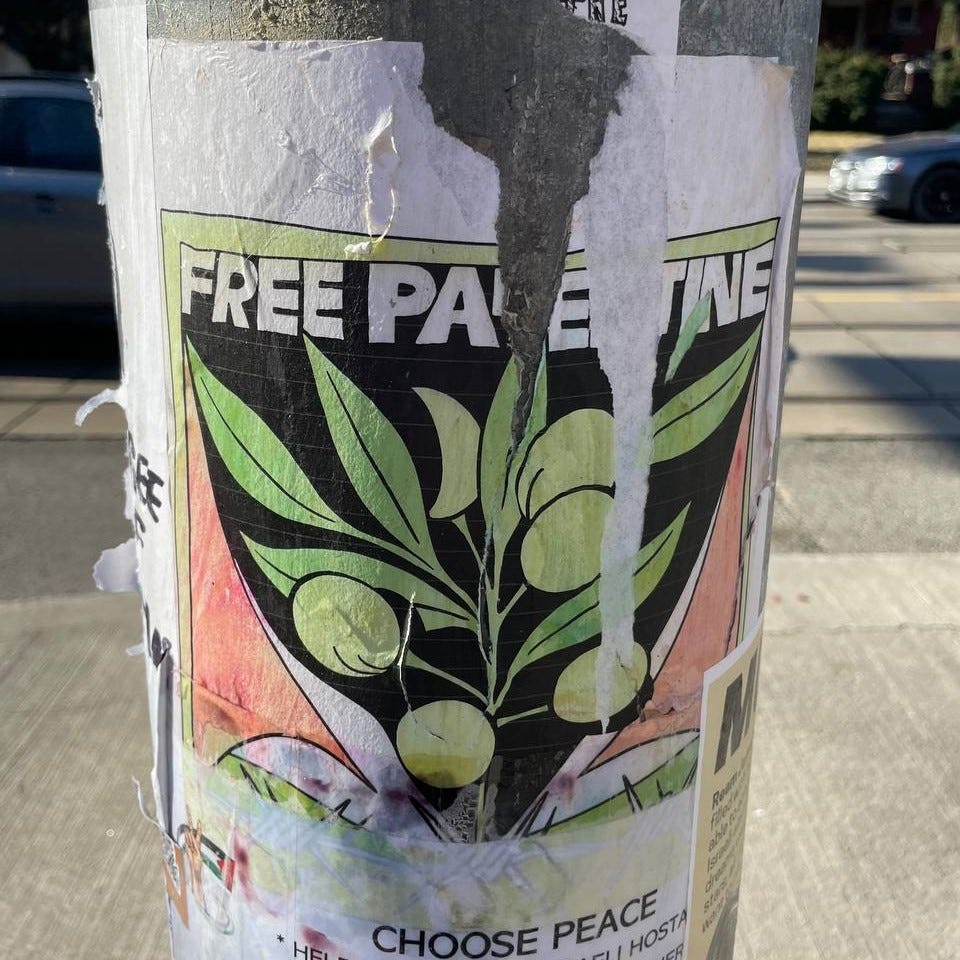

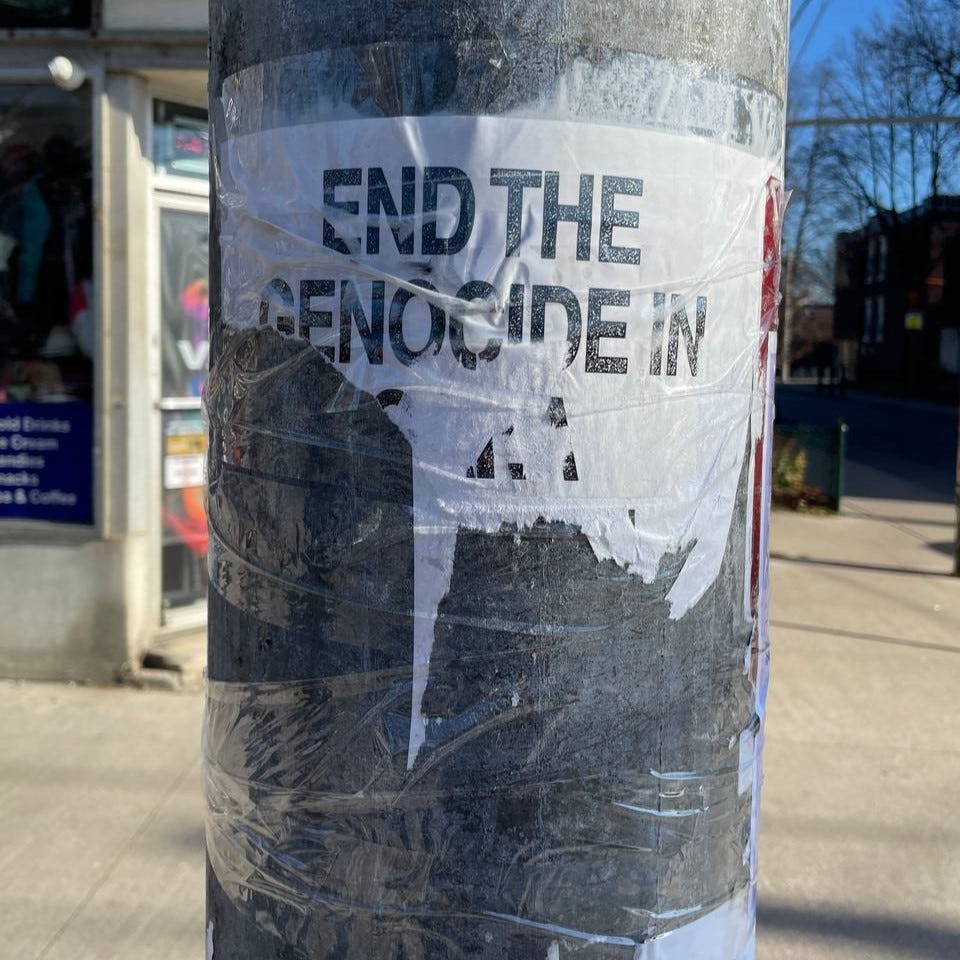

Lately, it gets dark early and even during the day the light is cold and blue. The only things worth eating are pomegranates and chestnuts, and squash. Yesterday, walking down Roncesvalles to purchase these fruits, I saw that many of the Free Gaza posters wrapped around the concrete poles had been defaced, the paper torn in uneven and violent shreds. I imagined the contact of the person’s nails on the cold concrete, trying hard to rip off the pieces of paper that said Gaza and Palestine and genocide. I thought about the emotion behind that act, the desperate attempt to obliterate not only the other but the truth of what is being done in your name. I imagine the thought is similar to a common vein we encounter in the Balkans: How dare they call it genocide, it is only mass killing, and they deserve it. Only we have been the victims of real genocide. We know it when we see it. On the poles were also new posters, beseeching the majority civilian population of what is essentially a ghetto to ‘lay down their guns’ to enable a future of ‘peace and love’ in the region. I think openly fascistic beliefs are preferable to this kind of fake universalism that invokes the name of love in vain.

What is wrong about the stance of why can’t we all get along is that it forgets that power exists. The only symmetrical thing about this conflict might be the amount of trauma and pain felt by all. But everything else is the result of a brutal, material asymmetry of the power to kill, maim, torture, and imprison. And yet the result of trauma, indoctrination, propaganda, and fear is to pervert the mind into being unable to see the truth about power – your own fear feels like the realest thing, realer than the real. So you angrily tear off the word genocide from a poster, because to let in the truth about the suffering being inflicted would undo all of the knots shoring up your identity, your sense of self, and they just keep getting tighter.

In A Poem of Force, Simone Weil says that “violence obliterates anybody who feels its touch.” The souls of the perpetrator and the victim are both rended on the teeth of war, crying for deliverance and yet bonded in destruction.

Violence is a serpent. Few are immune to the disease of power, regardless of whether they have at times been innocent, or been victims. But having experienced pain appears to so profoundly disturb the mind that one begins not just to deny the pain of others but to lay claim over it, taking it on as in a mirror.

Here is one instructive tale from the Balkans. This past summer, like all summers, was marked by anniversaries of various horrific chapters of the most recent war. In August was the anniversary of Operation Storm (Oluja), when the Croatian army forcibly expelled the majority of its Serb population, sending 20,000 civilians fleeing in long refugee columns, many on tractors, and killing about 400. This happened in 1995, as the new Croatian state’s closing act in the war, completing their ethnocidal campaign to rid Croatia of Serbs nearly entirely, with obvious echoes of the genocide it perpetrated against Serbs during World War Two. This forced homogenization happened under the auspices of the international community without, it seems, much protest, and many Serbs rightfully feel that no one has paid for the crime. At the same time, Oluja is one of the only crimes of the 90s that gets much memorialization in Serbia and the Serbian part of Bosnia (so-called Republika Srpska), because the victims are of the appropriate ethnicity to elicit sympathy. Like anything else, its memorialization is politicized beyond the point of disrespect to its victims; it is used to drum up the fear and trauma that bolsters the nationalist politicians who run the country and woven into a narrative of Serb victimhood that stems from 1389 (but is really a product of more modern nationalism).

This year, the nationalist leader of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, a man who threatens to restart the war whenever it feels convenient for him, held a memorial event for Oluja in the town of Prijedor. An odd choice, given that what Prijedor is known for in recent history is the systematic genocide of all non-Serbs in the area; the forced displacement, horrific concentration camps, and the unwillingness of authorities to let the victims memorialize these sites. To put Oluja on top of what Prijedor stands for (and is) is a game so putrid anyone can see its duplicity. These bad faith memorializations bring us further from a lasting peace - the same way that Remembrance Day glorifies war, death, killing, and betrays the victims of WWI, innocent boys sent to slaughter for imperial capitalist machinery. They keep violence alive, echoing through history. The rattlesnake tail of the serpent, raised and forever threatening to strike.

During his speech, the screen behind Mr. Dodik showed an image which was meant to personify Serb suffering. In it, a displaced woman holding her baby sits on a ramshackle bus with other women and children, looking desperately sad, harried, and preoccupied with worry. The photograph has a Renaissance painting quality – a sense of the eternal theme of the mother attempting to protect her child from danger.

Shortly afterward, it was revealed that the photograph was not from Oluja at all. In fact, it actually shows Sabina Mujkić with her baby daughter Nermina in 1995, two of the Bosnian Muslims who were expelled from the town of Žepa when it was overrun by Ratko Mladić’s Serb forces who had just taken Srebrenica and committed genocide there.

In 1995, over 4,000 Bosnian Muslim women and children were expelled from Žepa. It is documented that General Mladić himself would board the buses of terrified and hungry civilians and let them know that he was granting them their lives as a gift. (The men of Žepa were able to escape the fate of those in Srebrenica, as news had spread and they had fled and hid in the woods; as well as due to the heroism of local army leader Avdo Palić, who promised to be the last to leave the enclave after negotiating the withdrawal from the town and overseeing the safe evacuation of civilians. After voluntarily going to a meeting with Serb officials on July 27th, he was arrested, held in prison, and then never seen alive again. His remains were recovered in 2001.)

Simone Weil defines force as “that x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing. Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him. Somebody was here, and the next minute there is nobody here at all.” Being at the receiving end of force is to already be marked as a thing. The woman in the bus with her baby has been granted her life as a gift by the same man who removed her right to life in the first place.

Much was made of the mistaken use of the photograph. More than an embarrassing mix-up, it spoke to Dodik’s desire not only to deny that Republika Srpska’s army had ever caused pain, but to steal the pain of its victims for his own political profit. This desire is revealed in the first instance in the act of holding the memorial event in the same place where their own forces had perpetuated unthinkable crimes. Clearly craven, but extraordinarily common in the Balkans to inhabit what should be the space of your guilt and instead pave it with your victimhood. And this is possible, because for each act of violence, there is another example where the victim and perpetrator are reversed, and thus each group clamours to be recognized as the purest victim.

And does this not tell us the truth behind the apparent mistake? In fact, through his error, Dodik inadvertently revealed a much deeper truth. The photograph of Sabina may as well have been a photograph of Svjetlana. The woman and the baby are innocent. The suffering of the refugee expelled from their home is universal. These crimes are not permissible no matter who they are done to. The crime is called a crime against humanity – the victim’s humanity, the perpetrator’s humanity, all of our humanity. The pain comes from the same, common well.

Weil: “The idea of a person’s being a thing is a logical contradiction. Yet what is impossible in logic becomes true in life, and the contradiction lodged within the soul tears it to shreds.”

The fact is that we are each other. We could all look at this woman and see our mother. To see our mother is to be reminded of the equal sanctity of every single human being. Denying this tears our souls to shreds.

I love how your essays weave unexpectedly from one subject to another and then neatly wrap up in pretty bow at the end :)