The pure products of Yugoslavia go crazy—

no one to drive the car

Last week, I was pregnant with Schrödinger’s baby. That is, I wasn’t pregnant, but I didn’t know if I was pregnant or not. I went to get a CT scan, where they asked me if there was a possibility I could be pregnant. Technically, there was. It was a very slight chance, but the consequences (mandatory abortion due to radiation) were too dire to risk, so I opted to reschedule the appointment. I was to call them back when I got my period, which would confirm that I wasn’t pregnant. My period was late, as it always is, so I spent a week tossing around the possibility of my baby, which both did and did not exist. I knew I wasn’t pregnant, because I sensed a deep sameness within my body that I’m sure would not be there, but at the same time I could not confirm it. I enjoyed having the chance to contemplate this terrifying bodily transformation from within a hefty margin of certainty that I wasn’t.

My analyst wanted to know when I found out about sex and the whole mystery of the provenance of babies. Disappointingly, I could not remember such a moment. However, I remember in great detail the unnerving realization that my private parts would play an unthinkable role in my future life. Not sex, of course - the little I understood of it sounded reasonable - but rather, giving birth. Like most female children I believed that babies came ‘from the belly’ which on its own was not a troubling idea. However, when an older girl took me aside and informed me that in fact, babies come from your chicken (the Bosnian slang for vagina), I was horrified. Babies were obviously much too large for this to be true. I was unclear about how it all really worked, but it disturbed me. When I was older, I found out more, and I remained disturbed.

The discovery that babies come from the chicken is the only real traumatic shock of childhood that I remember. Not finding out that boys had penises and I didn’t, not finding out that sex existed nor that my parents had had it, or whatever other crucial psychosexual developmental moment.

I remain somewhat unreconciled with the idea that in order to be a mother, I have to undergo a total metamorphosis which results in cleaving into two beings. I don’t think that people born as men will ever understand the haunting element of this knowledge that your body does not belong to you, and is ever approaching its own destruction, a splitting, a grotesque and socially necessary disfiguration. The crucible of the pain of childbirth is less menacing to me than the changes implied in the entire process, some of which are irreversible. Meanwhile, the cost, to men, feels abstract.

The cleaving of the individual, the utter dependence of the child, are facts that run totally against the dominant liberal paradigm of individualism, and the way that our society is structured. Arguably the evolution both of our consciousness and our civilizations has gone far enough that our mammalian realities are difficult to stomach – both birth and death papered over, alienated, medicalized. Pregnancy in modern Western society feels as estranged from the real as buying a packaged lamb chop in a styrofoam package in a brightly lit supermarket, the blood and brutality hidden by a lie.

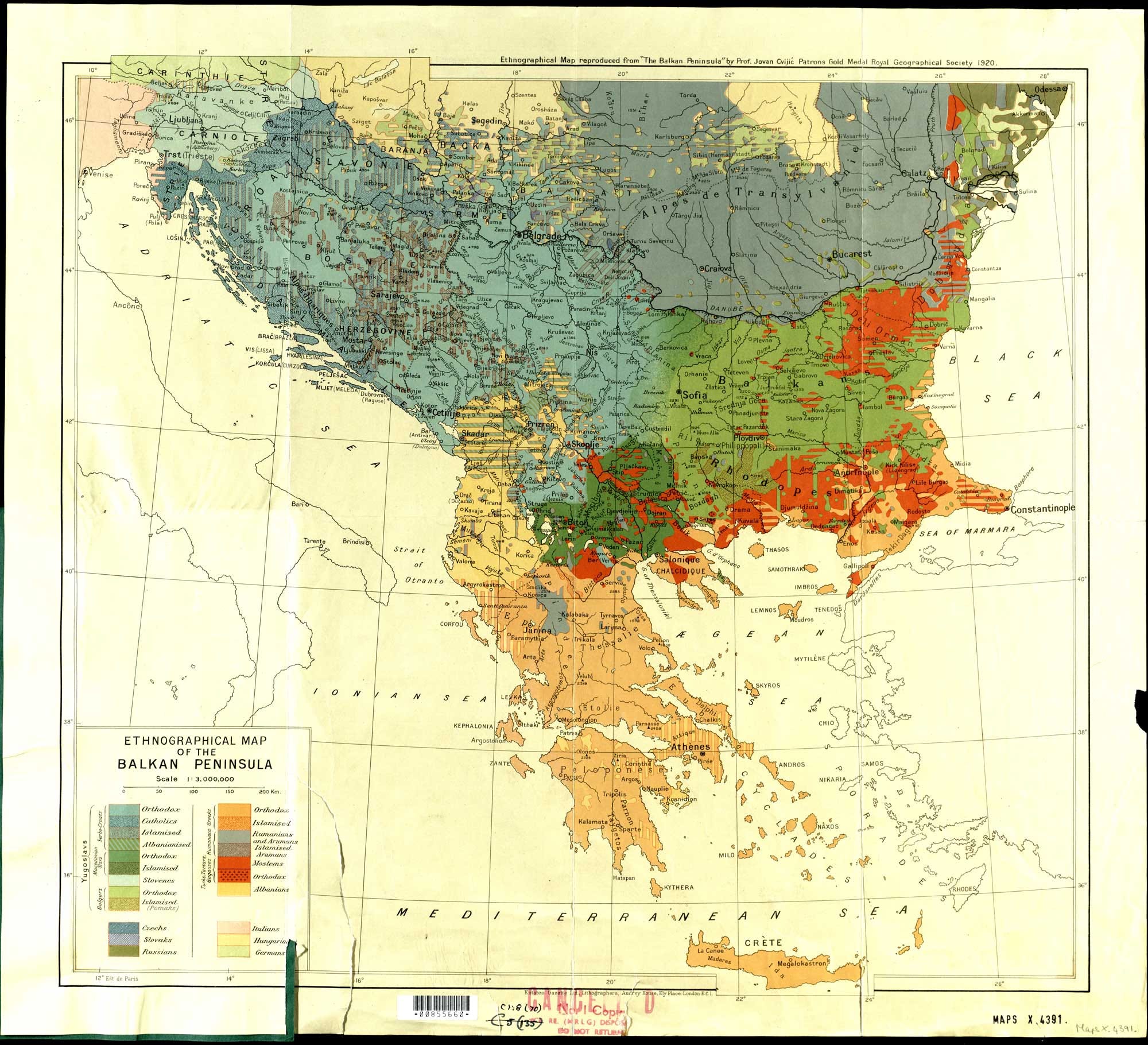

I’ve always thought that the very literal and embodied meaning of pregnancy is too far abstracted when we talk about things like declining birth rates or demographics in general. During my master’s, I was captivated by the idea that the very tissue of the womb can be consecrated as the territory of the ‘state’ - for example, if I ever get pregnant and give birth in another country, my womb counts as Canadian soil and the child would automatically have Canadian citizenship. The boundaries of state sovereignty can/are carried not just by land but people. In other moments in history, like during the Armenian or Bosnian genocides, the logic of sexual violence was inverted. Women were assaulted in order to create ‘Turkish’ or ‘Serb’ children - women’s bodies were seen as pure vessels through which men’s genetic material travelled to create a child who carried the father’s nationality, ie, ‘the enemy’.

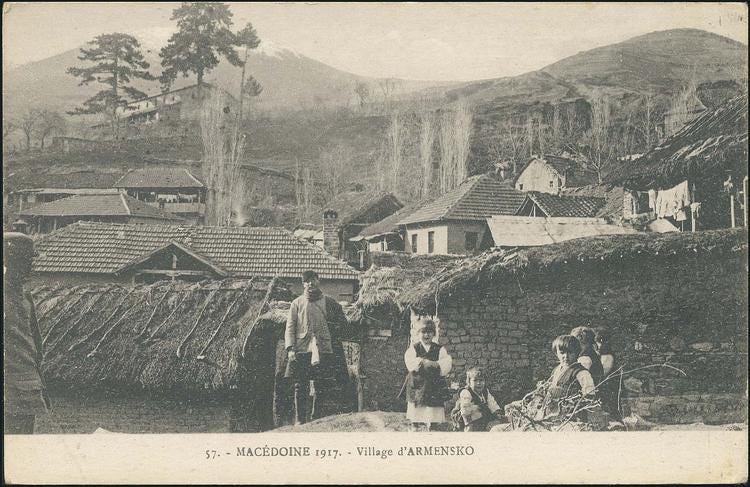

One of my favourite Macedonian songs is a love song that transposes the lover’s body across the towns in Northern Greece that are home to Macedonian Slavs. These cities were all lost to Greece during the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), and some people, like Chris’s ancestors, were left on the Greek side of the border. Their names were ‘Hellenized’ (Chris’s family from Mishov to Mishos), the cities and villages renamed (Lerin to Florina, Kostur to Kastoria, Voden to Edessa, Armensko to Alona), Macedonian language and songs forbidden. Greece has done such a formidable job of homogenizing their population that most people don’t know how diverse the country used to be - and is. The Albanian, Jewish, Macedonian, Turkish populations were displaced, replaced, killed, and/or ‘Hellenized’ into Greekness.

The love song is called Tvojte Ochi, Leno Mori. The object of desire is the lover, whose body maps onto the territory lost to Greece.

Your eyes are cherries from Voden.

Give them to me so that I can eat them!

Your face is a pastry from Lerin.

Give it to me so I can eat it!

Your lips are a box from Kostur.

Give it to me so I can open it!

Merak (passion, desire) and sevdah (longing) circle the song with a geographical lust. Is this a love song, or a nationalist song yearning for the land on the wrong side of the border? It doesn’t matter - the body is the land.

Nation-states as the primary method of organizing societies is one of my least favourite historical developments, not least because they now seem so ‘inevitable’. All the violence that went into (and still goes into) standardizing, defining, dividing people, hardening borders, creating ‘excess’ unassimilable populations (aka the birth of the modern state system in Europe) is as estranged from us as the lamb in the grocery store. Of course, the blood involved in maintaining it is still literal, from people drowned in the Mediterranean to the St. Lawrence River, but it’s made so we can easily ignore it, and in fact are supposed to.

The crusty blood at the edges of states is what international relations is all about. In a civil war, the creation of hard borders out of soft ones also implies blood. In a place like the Balkans, where people are so tangled up, creating these divisions also takes place upon their literal bodies.

During this last war, while women were in some way seen as containers for ‘enemy’ fetuses, or enemy territory to be conquered, men were dangerous carriers of an unwanted ethnoreligious identity. When men of battle age - aka reproductive age - were systematically murdered in enormous numbers in Srebrenica, this was considered a genocide, because the intention was to destroy them as a group. This considers the potential children these men could have fathered as part of that equation. The architects of the genocide raved about taking back Bosnia from ‘the Turks’ and cleansing the population. In reality, the people of Bosnia were so entwined that only horrific violence on all fronts could even begin to untangle them. The divisions that exist now are the result of war, not the cause of it.

Like many people from my hometown of Tuzla, my very existence belies the possibility of Bosnia’s division. My parents’ marriage is considered “mixed” – between a Muslim and a Serb – though you’ll find no two people who are less religious or identify less with any kind of ethnic identity. In the era of their marriage, and in their milieu, the question of ethnicity could not have been less important. Like religion, ethnic identity was something that secular socialism really tamped down, in some people permanently. (Though in a psychoanalytic analysis, some might say that the repression of ethnoreligious identity in Yugoslavia was what caused it, eventually, to rise from the dead. Badly buried bodies come back as ghosts, etc.)

My parents’ ethnic identities began to matter to people, as did my own - uncleansable and unassimilable. Something so absurd and unimportant became the difference between life and death. What my parents (with baby me in tow) fled was not just violence but the logic of war, which insists on rupturing the bonds between people to achieve some lunatic notion of purity.

My preferred political distinction is between those who seek to make distinctions and those who refuse. To put in your lot with humanity.

My friend Nidzara writes to me from Sarajevo:

The smells of somun bread and blossoms are in the air, the hyacinths are starting. All of this mixes with the pollution, but the spring is stronger.

The spring is stronger.

Brilliant as usual